Despite advances in medicine and massive increases in spending in America over the last several decades, there hasn’t been a corresponding improvement in health outcomes. One major reason for this is that there’s still a crucial element missing from the design of health care systems and services: consideration for the role of human behavior. That’s why, with support from the Commonwealth Fund, we examined behavioral challenges facing health care providers and explored a new model for integrating behavioral design into the innovation efforts of complex institutions – which we call Behavioral Design Teams – that has the potential to solve many of these challenges. We’ve published our findings in a new issue brief: Behavioral Design Teams: The Next Frontier in Clinical Delivery Innovation?

Just looking at the decisions and actions that both providers and patients encounter highlights the importance of designing health care to work for behavior. Providers must constantly assimilate abundant information and use their attention, memory, and judgment to make countless decisions in fast-paced settings each day; they must build trust with patients and repeatedly communicate vital information to people from different backgrounds who may be disoriented; and they must do all this in a taxing work environment requiring long hours, coordination across teams, and significant red tape. Meanwhile patients must understand and remember their treatments, form new habits, take the right drugs at the right time, avoid the wrong foods, persist through new struggles and pains, and more. Improving patient health and health care delivery depends not only on quality medicine, treatments, and advancements, but also on the decisions these two groups make and whether they follow through. Behavioral insights can help them do just that.

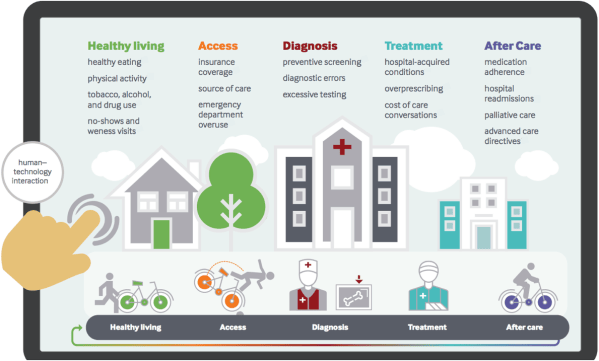

Behavioral insights have already impacted how health care is delivered and improved lives. One prominent example is the catheter checklist developed by Dr. Peter Pronovost. Inspired by pilot safety procedures reserved for emergencies, Dr. Pronovost simplified the guidelines providers use for patients who require central venous catheters down to an easy-to-follow checklist to prevent infection. Getting the most critical things right every time has proven to be better for patient health than physicians trying, and failing, to remember and follow dozens of minute rules. The checklist, adopted in hospitals across the country, has prevented countless infections – benefitting patient health and hospitals’ bottom lines, as new regulations increasingly tie incentives to key outcomes like minimizing hospital-acquired infections. There are many more opportunities to improve clinical delivery with behavioral insights. The diagram below illustrates some of these opportunities across the care spectrum, from preventative care, to diagnostic and treatment decisions, to communication and care after a hospital discharge.

Unfortunately, most efforts to improve care delivery by targeting human behavior are not systematic. However, there are several ways health care providers could look to integrate behavioral design. An especially promising model can be adapted from an approach governments have used to improve outcomes for citizens. Behavioral Design Teams (BDTs) have been embedded in governments at the local and federal level to improve operations and provide better services, including around several health behaviors such as flu vaccinations, medication adherence, and smoking cessation. The BDT model provides an ideal structure for rapidly solving behavioral challenges because it puts behavioral experts in close contact with domain experts and key resources, allowing them to soak up the intricacies of a new context while also driving culture change.

How would BDTs work in the health space? To give a taste of the how behavioral experts could help to address common health issues, we conducted workshops with three leading health care providers on explaining medication side effects adequately, avoiding unnecessary antibiotic prescriptions for acute bronchitis, and avoiding hospital readmissions after heart failure. Several insights came out of these workshops, which may form the starting place for designing new solutions. For example, together we uncovered that doctors feel pressured to provide something to patients, even when it’s unnecessary and harmful for public health; that nurses sometimes overweight the small risk that a patient will react negatively to hearing about medication side effects; and that the difficulty in shifting roles from medical expert to empathic caregiver may be one key driver of preventable hospital readmissions.

The potential impact of applying behavioral insights to health care delivery is immense, and the leading innovators have already begun taking the first steps. At we lay out in the issue brief, the next steps for improving health care entail finding a repeatable, reliable process for designing for human behavior systematically across the continuum of care. Behavior Designs Teams embedded in hospitals and other health settings can help drive that path forward, producing valuable new strategies for improving health care delivery and outcomes across the country.