A few months ago, I was walking down a street in the city where I live and stumbled upon a fallen tree blocking the sidewalk. I had three options: A) patiently wait until the coast was clear of fast-moving cars and walk on the street around it; B) put those arm workouts I’ve been doing to the test and try to move it; or C) take out my phone and report the problem to the government through my city’s citizen request app.

I chose option C. Citizen request platforms—also known as 311 systems in the U.S.—allow residents to report issues ranging from burst water pipes overflowing the streets to those potholes you never seem to be able to avoid while driving. You can even use these platforms to report if a public official asks you for a bribe! These technologies are at the cutting edge of governments’ interaction with residents, created in an effort to increase trust, satisfaction, and participation as they deliver a variety of services (financed by citizen tax dollars) in an accountable way. Citizen request platforms are used worldwide because they make it simple for residents to report an issue or request information, but more importantly, because these platforms provide regular residents—like me—with the ability to communicate directly with the local government. The process of reporting the fallen tree took less than two minutes. I had to include a brief description of the issue, a photo, and my location. Soon after that, I received a confirmation text message that the request had been received. Voilà!

But what happens next—when the request is received—is not always so simple. Despite 311’s enormous potential to improve government service provision, there is mixed evidence on whether the existence of these systems actually means safer roads, cleaner parks, or fewer downed power lines—not to mention more accountable public servants. The problem: residents across the globe are submitting thousands of requests daily, and yet governments are not able to keep up.

If user engagement cannot explain non-response, neither can a lack of resources, policy alignment, or political will. In fact, these platforms tend to be well-funded and installed in high-capacity government offices where there is an incentive for officials to deliver on their promises—considering they are working in a high-profile, politically-valuable, public-facing system. So, why does responsiveness remain a challenge in many cases around the world?

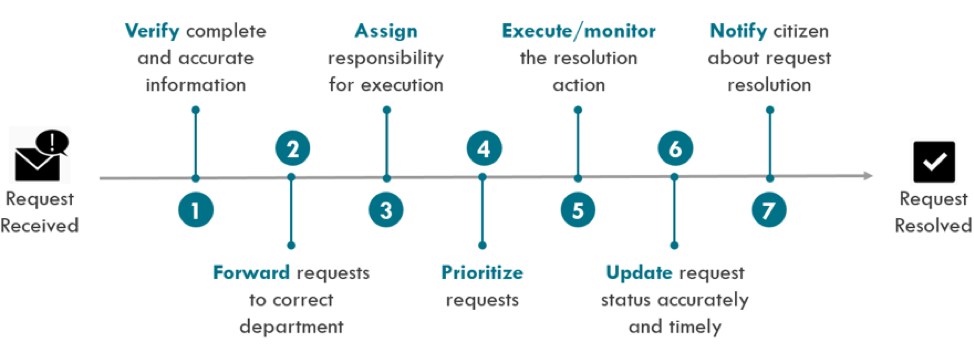

With support from the Hewlett Foundation, my team and I recently conducted a combination of site visits and interviews with more than 30 government officials, civil society organizations, and platform providers globally—in cities as varied as São Paulo, Delhi, and Cape Town—to find out. Although the process of resolving requests varies across cities, we found a series of seven steps that are common to nearly all government-owned platforms:

Behavioral science suggests that, like everyone, government officials often act the way they do because of how the environment around them—from office routine to features of the software they use—influences their ability to stay focused, make difficult choices, and translate intentions into actions. This chain of decisions and actions showcases the complexity of resolving requests, and a challenge in any one of the steps can significantly delay—in some cases indefinitely—the resolution of a request.

Below are a few examples of psychological phenomena that may be preventing government officials from responding to citizen requests effectively, as well as potential solutions to overcome them:

Highlighting teammates’ productive habits. Increasing communication between frontend teams (who input residents’ requests in step #1) and backend teams (who execute the action in step #5) could help ensure that both teams have the information needed to answer residents’ questions about a particular request at any point in time—leading to a more efficient resolution process and transparent communication with residents. Department officials may not be adding detailed enough notes about progress on the platform interface because they don’t see their coworkers doing it. People tend to behave as they perceive peers around them behaving. However, entering details into the platform is not a very visible act, so other officials may in fact be doing so. Creating a scorecard by department showing the number of high-quality notes entered in the system every month compared to other departments may lead to better update reporting and, therefore, higher quality in service provision.

Getting request status updates off the back burner. Officials may not be updating the status of requests correctly (step #6) or prioritizing them over other duties, and may be pushing this task until “later.” We know that people tend to report a greater willingness to undertake costly tasks in the future than their actual willingness to do these tasks when the moment arrives. Creating implementation plans, making externally visible commitments, or setting reminders or deadlines could help overcome this tendency.

Removing hassles. Citizen request platforms may be hard to use—unclear navigation menu, numerous request status options to choose from, lack of visuals and colors—and therefore could be creating an additional hassle when officials try to forward a request to the right department (step #2). Because people are significantly less likely to follow through on actions when they encounter seemingly minor obstacles, this design may lead officials to mark requests as “resolved” (step #6) when work still remains to be completed to avoid having to figure out an ambiguous forwarding process. Redesigning the platform to make the process simpler, more user friendly, and less time consuming could encourage officials to forward requests and/or update statuses more efficiently and effectively.

How can these insights improve government responsiveness? They show it is important to look closely at bureaucratic processes in order to understand their complexity and pinpoint where things can go wrong. Too often we assume, particularly when it comes to government processes, that if something is broken—in this case, the process of resolving residents’ requests—it will likely stay that way. But that doesn’t have to be the case, which is why we are embarking in an effort to improve service provision through applied behavioral science. We’ll partner with governments in developing countries to design behavioral interventions, test their impact, and scale them up to help government officials improve service provision—and respond to residents who alert them to problems.

Seven months since I submitted my request to remove the fallen tree, I still have not received an update informing me whether it was resolved. I’m quite confident that the tree was removed within weeks—if not days—of my request submission. But do I know for sure who did it or whether the action resulted from my request? I don’t. Improving government responsiveness is not just about getting more issues resolved, but also making residents feel heard. Achieving this can be the first step to increase civic trust, satisfaction, and participation.