March 7, 2023

Beginning April 1, 2023, people enrolled in Medicaid will have to renew their coverage for the first time in three years.

During the federally-declared COVID-19 public health emergency, people did not have to renew their Medicaid coverage. This continuous coverage ensured families had consistent access to health care. As a result, Medicaid enrollment increased by 20 million people since February 2020 to over 90 million current total enrollees. But when Medicaid’s continuous coverage provision comes to an end on March 31, 2023, 15 million people are at risk of losing their health-care coverage. While that prospect is worrying, states can leverage this moment to increase health-care coverage and promote racial equity by streamlining their Medicaid renewal processes.

Continuous coverage temporarily suspended the Medicaid renewal process, a process that was time-consuming and burdensome and too often prevented families from accessing health-care coverage. But when continuous coverage ends, enrollees will have to navigate existing and new barriers to renew their coverage:

- Many people who currently have Medicaid may be unaware that they must renew or are unfamiliar with the process.

- If a person’s contact information has changed, they may not even receive a notice to renew.

- During renewal, people may need to gather proof of income and other paperwork, such as tax returns, recent pay stubs, alimony, or proof of citizenship or immigration.

- People without access to a computer or internet may need to travel to renew their coverage in person.

- Anyone with questions about the process may experience long wait times, as state agencies will likely be under-resourced and overwhelmed by their new caseloads.

Around 7 million eligible people are at risk of losing their coverage because of the time, money, and other effort required to successfully renew coverage. These so-called administrative burdens will affect everyone, but they more acutely harm people with the fewest resources to overcome them.

These burdens also exacerbate existing racial inequity. Due to historical discrimination, people of color and immigrant populations are overrepresented in jobs that do not provide health-care coverage and are disproportionately covered by Medicaid. Therefore, they will likely lose Medicaid coverage at higher rates when these tedious renewal processes resume.

It doesn’t have to be this way. Historically, state policy makers have included more burdensome requirements in programs that disproportionately benefit people of color and people with low incomes. Yet policy makers did not include these same requirements in programs that disproportionately benefit white and middle- to high-income earners—like homeownership tax subsidies. While a person automatically gets the mortgage interest rate tax deduction when they complete their tax return, other income-based benefits—such as Medicaid, SNAP (Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program), and TANF (Temporary Assistance for Needy Families)—require people to complete separate, time-consuming forms. Burdensome requirements are a policy choice, and decisions about when to add burdens are often rooted in false and racist beliefs about why people experience poverty.

While unwinding the continuous coverage provision poses enormous risks to health-care coverage, it also presents an opportunity for states to improve their Medicaid programs. They can make the policy choice to reduce administrative burdens and test new ways to increase coverage. This will not only mitigate the anticipated harms of the unwinding process, but it can also address historical forms of injustice and advance racial equity.

What can states do to mitigate unwinding?

As the continuous coverage provision comes to an end, states can take several steps to reduce administrative burden in Medicaid and maintain health-care coverage:

- Maintain continuous coverage wherever possible: The easiest way for states to reduce administrative burden is to maintain burden-free, continuous coverage for as many people as possible, regardless of income fluctuations or other changes during these specified periods of time. This might include, for example, coverage periods of 12 months, 24 months, or several years for certain populations, including postpartum individuals, young children, formerly incarcerated people, or adults who are chronically unhoused.

- For those that must renew, make the process easy and simple: To reduce the burden associated with renewal, states should increase the number of people who are automatically (or ex parte) renewed. That is, states use available information to verify that certain people are still eligible without requiring them to submit additional paperwork; for example, people who qualify for other benefits programs like SNAP or TANF, or for those who previously reported no income. States can also hire more staff to cut wait times and make it easier for people to renew coverage.

- Test new programs and policies explicitly designed to advance racial equity: Many states have (and should continue to) experimented with ways Medicaid funds can address the social determinants of health and reduce racial health disparities. Enhanced benefits could, for example, provide access to housing, healthy food, employment, transportation, child care or family care services, and more.

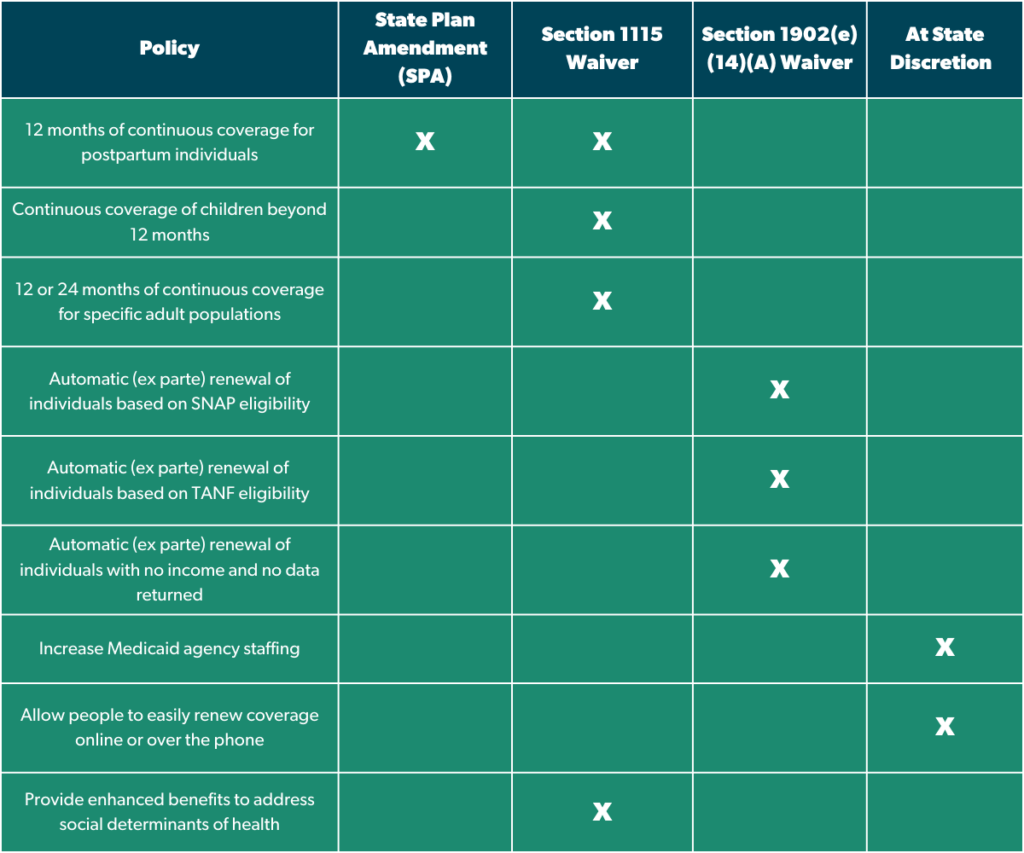

[See below for a chart of the different policy levers states can utilize to implement these policies]

Finally, as states begin their unwinding process, it is critical that they measure and report coverage losses, application numbers, average wait times, and more. In addition to following federally mandated reporting requirements, states should be as transparent as possible and release data as soon as it is available. States must use this data to evaluate their unwinding efforts and iterate as needed to improve their programs, expand coverage, and advance racial equity.

Actions States Can Take During Unwinding

- State Plan Amendment (SPA): States submit a State Plan Amendment to the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) to gain approval for proposed permanent program changes.

- Section 1115 Demonstration Waiver: States can submit Section 1115 waivers to the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) to gain approval for experimental, pilot, or demonstration projects designed to implement and measure new policy approaches to improve their state’s Medicaid program.

- Section 1902(e)(14)(A) Waiver: States can submit Section 1902(e)(14)(A) waivers to temporarily support their unwinding process following the end of the COVID-19 public health emergency and the Medicaid continuous coverage provision.

- At State Discretion: These are policies that state Medicaid agencies and/or other state entities can take that do not require federal approval.

We’ve seen that health-care policies intended to be temporary stopgaps during the COVID-19 public health emergency actually make for good, longstanding policy. While these protections may soon be rolled back, state policy makers and advocates should use this moment to implement new policies that get more people the health coverage they need.