“Nora, put on your shoes. Nora, put on your shoes. Nora, put on your shoes.” I’ve been asking my six-year-old to get her sneakers on for the last 15 minutes, and she’s definitely tuned me out while she scampers around the house. I’m complaining to my friend about it later that day, and she offers some counterintuitive advice: “Give her less time.” She says she’s flipped the approach at her house: she asks her son once, with sneakers in hand, and nowhere else for him to go.

It turns out that my friend’s instinct here is a smart way to change behavior—though it may seem surprising at first. It’s easy to think that more time equals more chances for people to notice, learn, and act. But often, less time actually leads to more action.

That insight also applies in higher-stakes situations than my daughter’s wardrobe. “I’m worried 2 weeks isn’t enough time. Should we make it 3 or 4?” My friend is planning a fundraising campaign, and she reasons that more time will give people more opportunities to hear about the campaign, to learn about the impact her organization has, and to actually make donations. But she’s falling into the same common trap: assuming that more time will lead to more attention and action.

My friend isn’t the only one dealing with this problem. Effectively capturing and using moments of attention is critical for fundraising as well as many other efforts to improve systems, but we can only convince people to act if they notice us. Getting people’s attention is harder than it seems. We know humans have limited attention. We have to stand out in a world full of shiny things (and internet tabs) trying to capture our focus. So what works?

How to capture attention

Aim to forge a close link between grabbing your audience’s attention and making it possible to act. And you probably don’t need as much time as you think. For Nora, that means providing the sneakers right after breakfast and remaining present until they were on her feet—offering less time for more action.

For my fundraising friend, that means streamlining her campaign. Especially when it comes to giving, people want to do good—and they often need far less information and time to act on it than we expect. In fact, providing too much of either can cause people to put off giving.

We saw a great example of this in our collaboration with Raised By Us, an organization that runs workplace fundraising campaigns. We helped them incorporate behavioral insights into their innovative employee engagement programs. One of the most interesting findings was that more people appeared to donate when Raised By Us reduced their standard two-week deadline for giving during a fundraising campaign to a few bursts of engagement (either a single 90-minute period on one day or as little as 15-minute chunks on successive days) totalling under 2 hours.*

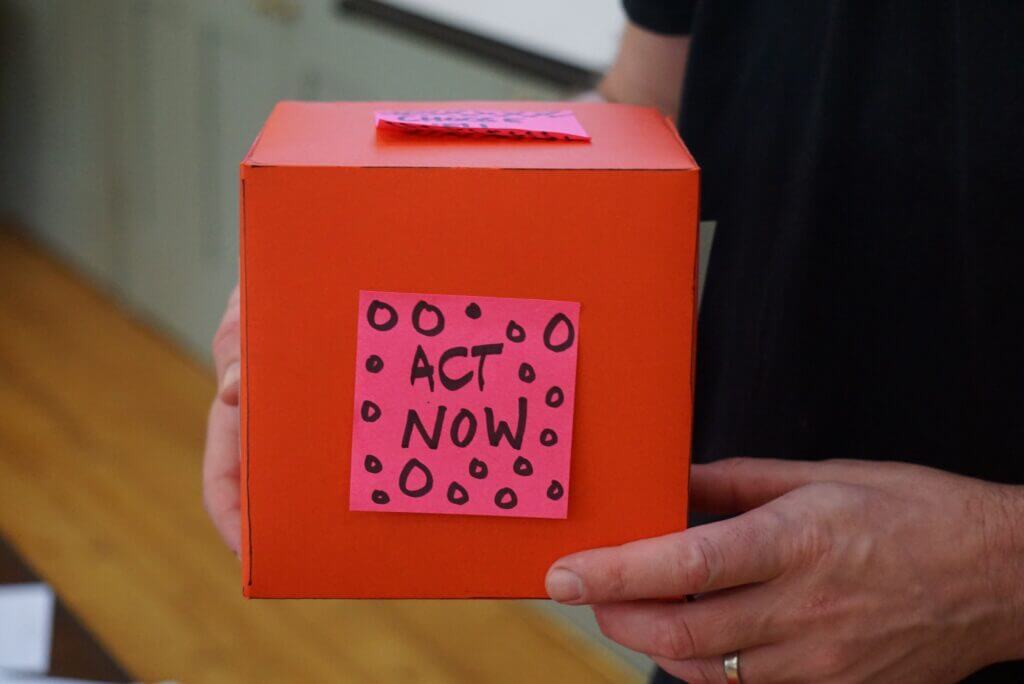

Time-bound fundraising campaigns like this are in part effective because they focus attention. When people have long time horizons, it’s easy to put off giving till later, and when people do that they’re prone to forget or change their minds. When there is no later, people are more inclined to act now.

More broadly, this finding underscores the behavioral insight that everyday giving is often impulsive. When we shorten the window for giving, we hone that impulsivity, in a sense encouraging people to speed up (which facilitates their generous impulses) rather than slow down (which increases the chance of distraction and perpetual procrastination).

The surprising upshot is that offering people less time or content may be just what they need to activate their most altruistic selves.

As for me, this morning I waited with sneakers** in hand for Nora to finish breakfast, then handed them to her and patiently stood by. Result? An early(ish) departure for school! A small victory, underlining that sometimes, less truly is more.

* Raised By Us did experiment with other tweaks as well, which may have contributed to the increased participation. In addition, the campaigns were run at different companies. However, insights from behavioral science and attention suggest the general finding is promising.

** If you’re wondering about socks, I’ve already solved that one behaviorally; my two kids share 24 pairs of identical white socks that are stored in a box by the door. No choice conflict and limited hassles for everyone!